Interview: Playwright Amanda Whittington

HTSA Admin

HTSA Admin

HTSA Admin

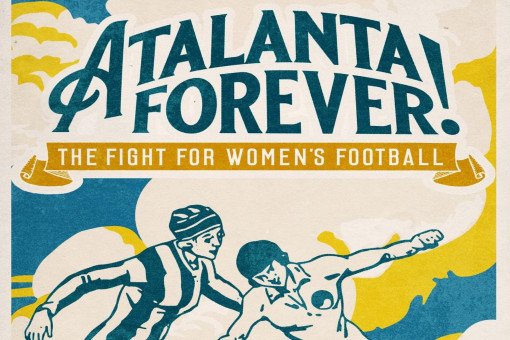

Earlier this month, we spoke to playwright Amanda Whittington about her play Atalanta Forever, a semi-fictionalised account of women’s football in Huddersfield leading up to the F.A. ban. Mikron Theatre toured the play over the summer.

If you missed it, don’t worry: The University of Chichester Conservatoire has teamed up with Amanda and Mikron to develop the play for a main-stage production, which will run in March 2022. Get your tickets here.

--

HP: What moved you to write a play about a women’s football team other than Dick, Kerr Ladies, whose shadow always looms large?

AW: Exactly that reason. Dick, Kerr Ladies seemed to be the beginning and end of the story of women’s football.

I originally talked to Mikron Theatre about working together on a play. They have a strong identity and interest in social history and social justice, as do I, especially when it comes to female-centred stories. So, we discussed some historical figures in our first meeting and Lily Parr came up. Lily was a woman with whom I very much identified because I’d been a keen footballer as a child in the seventies and was aware of the repercussions of the ban even then.

I started reading about Lily and Dick, Kerr, and all of that, and quickly realised that the story had already been well documented. Gail Newsham unearthed the story for her book, In A League of Their Own, and there are other excellent accounts of the club’s history. For the purposes of the play with Mikron, I wanted to find a new angle, and, of course, Dick Kerr were only as good as the teams they played. Without them, there wouldn’t have been a Dick, Kerr Ladies. So, I started thinking, well, who were they, all these teams of women across the country, and what’s their story?

Living in Huddersfield, and with Mikron being based in Marsden, I focused my attention locally, and came across Huddersfield Atalanta Ladies. There were a couple of team photos and some references to them in the general history books about women’s football, but very little about the personalities involved. As a dramatist, that was quite helpful because it allowed me to create and invent around the established facts. In terms of writing a play like Atalanta Forever, you want the skeleton of the story to be factual, but you also want to explore the unanswered questions.

That’s why I found Atalanta so fascinating. Then there’s the fact that, when you’re writing about sport, the underdogs and also-rans and minnows are always more interesting than the star teams and players. When I saw that Dick, Kerr walloped Atalanta 10-0, I said to myself, I want to know more about them! What was that like, to be on the other side of that pasting?

I wanted to resurrect a near-forgotten club and their stories, so I did. It was good fun. We had the fixture list and a few names, including Constance Waller, but that was about it, really. I looked around to see what was about in Huddersfield at the time. Standard Fireworks was a big company, so I decided that one of the players would work there. And I happened upon a quote from a former play who said the team was a mixture of working and middle-class women, so I thought, again, that’s an appealing perspective. The fact that they were named after a Greek heroine was attention-grabbing, too.

To focus the story, I imagined a friendship between a working-class woman, who worked at the fireworks factory, and a middle-class woman, who was a teacher. They bump up against one another in this team, crossing social divides, which they probably would never have done otherwise. Those were the threads I picked up on to inspire the characterisations in the story.

HP: How imposing, if at all, was the spectre of the F.A.’s 1921 ban on women’s football when you were writing?

AW: The ban gave the play its sense of drama. It always raises the stakes when the audience know something the characters don’t. You know that the tsunami is coming for them, and that knowledge plays against their hope, their optimism, their dedication to football and the team.

It’s one hundred years ago, but it feels like we’re only just turning the corner. As I said, I played football as a child. There was no way that I could have progressed as a player beyond the age of 11 back in the seventies. Going up through senior school and into my twenties, it was a completely closed door, and a significant one in terms of personal freedom and choice. Girls couldn’t progress in the game simply because of their gender. That’s changed in my adult lifetime and it’s a change that I wanted to celebrate, even though we’re still fighting those battles for equality. It’s only in the past decade or so—even the last 5 years—that women’s football has received the recognition, status, and support that it briefly enjoyed a century ago.

HP: You mentioned that Constance Waller was, in effect, a blank canvas. Did you read or see anything that gave you an idea who she might’ve been, even if it was implicit?

AW: I knew she was the founder of and spokeswoman for Atalanta Sports Club. She hadn’t specifically set it up as a football team. They did all sorts of other things—cricket, water polo, and so on—and I’m not entirely sure how or why they got into football. I devised a narrative with Ethel from Standard Fireworks, who turns up and challenges the middle-class women to kick a ball around with her.

I thought, if Constance had named this club after a Greek goddess, then she was likely drawn to the classics; to have set up a ladies sports club shows she had a strong sense of purpose. We often assume that women’s teams were all factory teams, but that wasn’t the case in Huddersfield. Constance, perhaps, had a more intellectual, academic perspective on women and sport, which is what I enhanced and embellished when writing her.

In the aftermath of the First World War, there was a belief that sport was a sort of morally cleansing undertaking—one that was as good for the mind as it was for the body. I decided that Constance would have exemplified this philosophical, almost spiritual attitude towards football. It was nice to highlight a side of sport that we don’t really talk about or believe in anymore.

In the end, though, while the play is based on fact, it’s predominately a work of fiction and imagination.

HP: Why do you think that it’s important for women such as Constance to be rescued from obscurity?

AW: Because we still haven’t achieved anything like equality in sport.

It’s incredibly important to know the wider history, to know how long women have been fighting simply to play. So much of women’s history is unrecorded, ignored, or undervalued. I think that we should take any opportunity to right that wrong.

I mean, look at the Dick, Kerr match against St. Helens at Goodison Park that drew 50,000 people. Women’s football wasn’t a gimmick or novelty. The women were good, and people recognised it. It’s been a hard-fought victory, and a profound one—just look at all the girls and women who are playing football today, from the grassroots right up to the Lionesses. But there’s still a way to go—the experiences of Constance and others like her might provide the inspiration to strive for more.

HP: Why do you think women’s football was banned in the UK?

AW: I didn’t want the play to say that men were at fault. It wasn’t that simple.

During the war, with the Football League suspended and so many men away at the front, women stepped in to fill a gap. They began playing with the aim of entertaining the public, yes, but their main goal was to raise money for wounded soldiers. After peace was declared, Britain and many other countries had to contend with an unparalleled level of trauma caused by so many deaths and injuries. Masculinity itself had also been dealt a huge blow.

There was this belief, then, that British society must be rebuilt and reinvigorated. Politically, it was decided that this meant women fulfilling their traditional roles as wives, mothers, and daughters. They were expected to go back into the home, raise the next generation, and by doing so, heal the country. Family and domesticity were seen as the most obvious way to recover from the national distress inflicted by the war. There were also fears about the new post-war woman, epitomised by the Flapper Girls of the 1920s. They were perceived to be more independent, sexually liberated, and thus less likely to do their familial “duty”. Football was tarred with the same brush, namely the fear of women who don’t ‘know their place’.

I try to understand the ban in this context. When it was necessary for the war effort, the people in charge encouraged women to work and play football and do other things that men do. As soon as the war was over, the national objective was to get back to “normal”. But of course, the genie wasn’t going back in the bottle—and that’s where the drama lies in our play.

HP: You touched upon the charitable aspect of women’s football. That was certainly something that Atalanta embraced. Did you know much about that?

AW: Atalanta raised a great deal of money for the Mayor’s Distress Fund. In fact, by today’s standards, they raised huge amounts.

They left a significant financial legacy, with the money they raised still being distributed in the late-1920s.

HP: Funnily enough, after Atalanta played Paris Féminines at Fartown, the Mayor of Huddersfield invited both sides and the men’s team to a dinner at the Masonic Hall in Greenhead. Were you aware of this and the other links between the male and female players when you decided to include Town icon Billy Smith as a character?

AW: I found out early on in my research that the Huddersfield Town players hosted joint training sessions with the Atalanta women and were very supportive. I loved that. That’s been my experience of football, too. It’s not a simple case of men not wanting women to play—that’s a stereotype I wanted to explode.

HP: Well, presumably a lot of men were happy with women playing football, because tens of thousands were paying good money every week or so to watch them.

AW: Exactly!

HP: Finally, what was the reaction to the play?

AW: I was quite surprised by how many people weren’t aware of the ban. I think there’s an assumption that women’s football had been around in some shape or form for a long time, but people didn’t realise it was actually banned from FA grounds, or how big a draw it was during and immediately after the First World War.

I think audiences found the idea of the ban quite extraordinary. In 2021, it seems inconceivable, which shows how far we’ve come. But like I said, there’s still further to go and even more for women’s football to achieve.

--

Find out more about the history of women’s football in Huddersfield by browsing our two dedicated primary source collections: Women’s Football Archive and Women’s Football Timeline.

If you are interested in supporting Huddersfield Town Women, their website can be found here, where you can stay up to date with results, team news, and match reports. You can also help sponsor women's team players, who have to pay to play.